Venezuelan children and adolescents in Colombia have the right to access the country’s educational system regardless of their documentation or migratory status. Even so, they face challenges related to educational inclusion like overage, which occurs when a student is older than the traditional school age for his or her grade level. Accelerated learning models can be used to address this issue and help students reach their expected grade level.

According to the United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR), Colombia is the country with the highest number of Venezuelan migrants and refugees. As of October 2022, the Inter-Agency

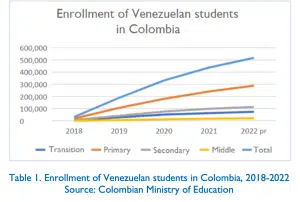

Group for Mixed Migratory Flows (GIFMM) estimated that there were nearly 2.9 million Venezuelan migrants in Colombia. All of Colombia´s social and economic sectors have had to respond to this massive migration in a very short period. For example, the Colombian Ministry of Education reported that a number of students from Venezuela that the Colombian education sector has needed to integrate rose from 34,000 in 2018 to 580,000 in 2022.

The problem of overage arises when there is a gap of two or more years between the student’s age and the age at which the student is expected to study in a certain grade. For example, one expects that a student in first grade will be between six and seven years of age. If the student is nine or older, he or she is regarded as an overage student. Migration directly corresponds to overage because the time spent migrating causes children’s and adolescents’ education to be interrupted and because they can face difficulties accessing the educational system in their host country.

In this regard, overage can affect the social and economic integration of Venezuelan children and adolescents and their families into Colombian communities. It is more probable that students experiencing overage will be ridiculed, a situation which, for migrants and refugees, may be further aggravated by xenophobia and discrimination. Thus, the problem of overage, combined with acts of discrimination, increases the possibility that migrant and refugee will students drop out of school. In turn, this will limit their access to technical and higher education, opportunities for employment, and mid- and long-term integration in their host community.

According to GIFMM, in 2021 92,941 students from Venezuela, representing 22 percent of Venezuelan enrollment in Colombia that year, were in the condition of overage. This is a worrying figure when compared to the percentage of Colombian overage students, which was six percent. This situation underlines the importance of formulating strategies to integrate Venezuelan children and adolescents in education, not only by improving their access to the educational system, but also by increasing the use of relevant educational models that respond to migrants’ unique needs and circumstances.

In a study done in Colombia and published in 2020, the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) found primary challenges for providing education to Venezuelan children and adolescents. These challenges were: 1) limited spaces, or quotas, for students in public schools; 2) limited availability of teachers; and 3) limited access to accelerated learning models.

Regarding how the complex conditions that migrant populations face can cause barriers to children and adolescents access to, and permanence in, the educational system, UNESCO noted:

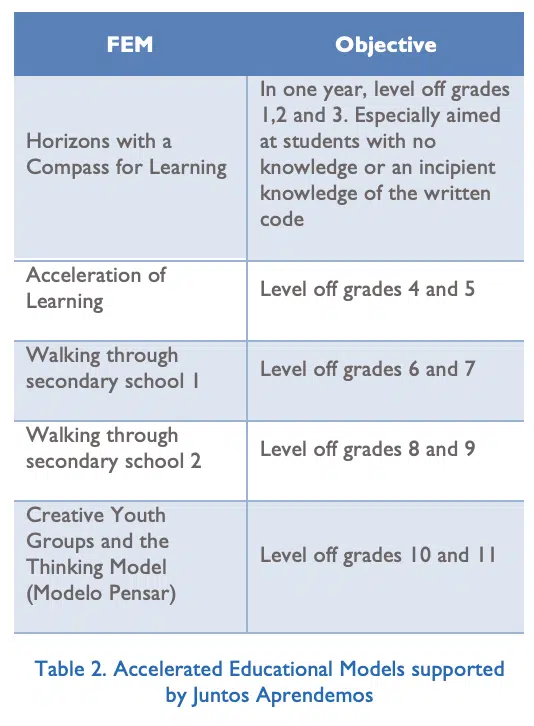

To this end, accelerated learning models are essential to the integration of Venezuelan children and adolescents. These models use participatory and project-based pedagogies to engage students, families, and teachers, and to improve learning environments. Accelerated learning also helps establish a close relationship between teachers and students’ parents and caregivers, create strategies that respond to students’ particular needs, and make it possible for the parents and caregivers to think of the school as an integrating space, based on a greater involvement with the education of their children.

An example of the positive impact that accelerated learning can have on migrant inclusion can be seen through Jeremías’ experience in the Pedro Fortoul school in Cúcuta, Colombia. Jeremías is a migrant from Venezuela and his education was interrupted on several occasions when he migrated with his family to Colombia in search of new opportunities. After a long time without studying, Jeremías enrolled in an accelerated education program implemented by the Juntos Aprendemos project, or “Together we Learn”.

Through this program, Jeremías earned one of the highest grades in his class and he was able to transfer into a traditional education program with students his same age and at his expected grade level. Jeremías is now on the way to completing his educational trajectory and developing stronger roots in his community and the country.

Despite stories like that of Jeremías, there is still a long road to travel before the provision of accelerated learning models will satisfy the needs of the country. Through a study of accelerated learning model use in six Colombian cities impacted by migration, Juntos Aprendemos found that 80 percent of the students in the condition of overage are not enrolled in accelerated education. Instead, these students study in a traditional classroom where they receive an education that is not adjusted to their needs or circumstances, and as a result, this increases the risk of their dropping out.

In Barranquilla, for example, Juntos Aprendemos supports 114 accelerated education classrooms, making it the city with the highest number of accelerated education classrooms in the country, over 300, and helping it act as a model for other cities in Colombia.

In Cali, Juntos Aprendemos assisted with the establishment of new accelerated education classrooms at all educational levels, making it possible for students to progress from one grade to another. Juntos Aprendemos also works with local and national education actors, including Secretaries of Education, to improve their provision of accelerated learning.

In September 2022, the Cúcuta Secretary of Education, with the support of Juntos Aprendemos, issued Resolution No. 03478. This resolution enables any public education institution to provide accelerated education to students. One of the models approved by the Secretary of Education is “Horizons with a Compass,” a model developed by the Carvajal Foundation that has been improved and scaled up through Juntos Aprendemos.

In 2023, Juntos Aprendemos will continue to strengthen accelerated education models in Colombia, recognizing the impact that these models have on migrant and refugee children and adolescents. Within this framework, it is crucial to highlight Juntos Aprendemos’ work with the Accelerated Learning Models Working Group (ACCESS), led by the Norwegian Refugee Council, to which 20 governmental and non-governmental entities belong. Through ACCESS, Juntos Aprendemos is strengthening coordination between educational actors, and it is accompanying the Colombian Ministry of Education in its application of accelerated education models. Juntos Aprendemos also joined the Inter-agency Network for Education in Emergencies’ (INEE) Accelerated Education Working Group (AEWG) in 2023, which will allow the project to exchange lessons learned and best practices for accelerated education with experts from around the world.

May 18, 2023